Lotta Svärd in English

Visit the Lotta Museum

The Lotta Museum is a specialist museum of national significance that is located at an historical villa by the Tuusulanjärvi lake. The museum documents the history of the Lotta Organization and studies the voluntary work of women as part of the development of the Finnish society.

The Lotta Museum offers an introductory video, which covers all of the major themes of the main exhibition, Lotta Svärd – 100 Years of Societal Responsibility.

The introductory video must be booked in advance. The payment is 20 € + entrance fee (per person).

Contact the Lotta Museum’s customer service team at: info(at)lottamuseo.fi, tel. +358 (0) 09 274 1077

Establishment of the Lotta Organization

The Civil Guard Organization was a voluntary organization engaged in civil defence work in Finland from 1918 to 1944. In 1927, it formally became a part of the Finnish Defence Forces. Local Civil Guards formed home troops whose wartime responsibilities included mobilisation on the home front. Civil Guard men of service age operated in the units of the Finnish Army.

The Civil Guard activities also encouraged women to participate in civil defence work, and women became responsible for ensuring that the local Civil Guard men were ready for action, primarily in terms of clothing. Women’s sewing clubs were established in many towns and villages and attached to the local Civil Guard.

By the end of 1919, there were almost 200 women’s divisions. Commander-in-Chief of the Civil Guard, Didrik Von Essen, began planning a nationwide women’s organization to bring together all the activities of the women’s divisions in the Civil Guard. The women’s divisions of the Civil Guard became a nationwide association in 1921.

Lotta Svärd and the tales of Ensign Stål

The name of the Lotta-Svärd Association was inspired by a poetic work written by Johan Ludvig Runeberg, The Tales of Ensign Stål. One of the poems is about a soldier’s wife, Lotta Svärd. Lotta Svärd follows her husband to the battlefields during the Finnish War (1808−1809) and adopts the task of caring for and encouraging the soldiers.

In his speech in 1918, General C.G. Mannerheim likened the women who took care of auxiliary duties during the war to Lotta Svärd.

”Sisters of Mercy and the Lotta Svärds on the battlefields, and women working tirelessly at home in order to provide equipment and food for the soldiers, Finnish women have worked hard everywhere, in all sectors…”

The association was registered in the Register of Associations under the name Lotta-Svärd Association. In 1941, a rule change was approved, and the name of the association was changed. The hyphen and the word association were removed. From now on, the name was Lotta Svärd Organization. Unofficially, the name Lotta Organization had already been used before the Winter War.

Lotta Organization’s Divisions

The Lotta Organization was organised in divisions. The key divisions were defined in the rules as early as in 1921. The divisions permeated all levels of the organization, and the highest authority in the organization, the Lotta Svärd Central Board, issued precise instructions regarding the tasks of the divisions. All members of the Lotta Organization had to belong to a division, but, particularly in wartime, many Lottas took care of tasks in various divisions simultaneously.

In the divisions, the Lottas were divided into two categories: Acting Lottas (later, Field Lottas) and Service Lottas. Both entailed a requirement for active service. Field Lottas were obliged to leave their local area and be posted wherever help was needed, whereas Service Lottas took part in Lotta activities on the home front.

Administration

The Lotta Organization was based on districts and local chapters. The highest authority lay with the Central Board that was responsible for the leadership of the Lotta organization in accordance with the wishes of the Commander-in-Chief of the Civil Guard.

Practical operations in the organization were the responsibility of the heads of divisions and local committees, whose final plans had to be approved by the Central Board.

Renowned as an important power and a valued leader in the Lotta Organization, Fanni Luukkonen was elected the chairperson of the Lotta Svärd Central Board in 1929. Luukkonen was a qualified teacher, making it natural for her to lead by example. Fanni Luukkonen served as the chairperson for 15 years, until the Lotta Organization was disbanded in the autumn of 1944.

Ideology

The values of the Lotta Organization centred around religion, home and country. In the organization, it was also important to respect and value the work of the previous generations.

The guiding idea in the activities of the organization was that individuals become significant only when they are a part of something bigger. In order to build the Lotta identity, members had set goals in terms of education, morals, behaviour and appearance.

By mid 1920s, the organization’s guiding values had been recorded in a collection of 12 guidelines, the Golden Words.

Politics

As a result of the war in 1918, society in Finland was starkly divided into winners and losers. The Lotta Organization was not politically committed, but the ideology was strongly connected to the values of conservative Finland and anti-communism. As late as in the 1930s, attempts were also made to prevent cooperation with the social democrats, and Lotta Organization members shopping in socialist-run shops were frowned upon.

The increasing need for help resulting from the Winter War brought women’s voluntary organizations closer to each other. Work evenings were now attended by women from the Women’s Rural Advisory Organisation, the Martha Organisation, the Lotta Organization and the Social Democrat Working Women’s Organization. In February 1940, the Lotta Organization reached an agreement with the Social Democrat Working Women’s Organisation that allowed women to be members of both organizations.

The government’s attitude toward the Lotta Organization was strongly linked to the attitude toward the Civil Guard, as the Lotta Organization rules stated that the organization was committed to supporting the Civil Guard Organization.

As the Civil Guard gained more status, the Lotta Organization’s activities in voluntary relief and aid work also became more recognised.

Non-combatant organization

Commander-in-Chief of the White Army, C.G. Mannerheim did not encourage women to carry weapons. He felt that fighting on battlefields was reserved for men. According to Mannerheim, women were expected to help with caring for the sick and wounded, maintenance of equipment, duties on the home front, and comforting those who lost loved ones due to the war.

The statement of the Commander-in Chief played a key role in the development of the Lotta Organization into an non-combatant civil defence organization. The civil defence work carried out by the Lottas was versatile relief and aid work. Though Lottas, in general, did not take part in armed combat, in the summer of 1944, in order to ease the shortage of men, Lottas formed the 14th Searchlight Battery Division for the 1st Anti-Aircraft Regiment. This was the only military unit comprising women that was active and ready for combat during the active years of the Lotta Organization.

Lotta publications

In 1928, the Lotta Organization’s magazine was founded. In terms of editorial content, the magazine was absolutely loyal to the army and the foreign policy of Finland. This is why the magazine was rarely censored, unlike many other publications in wartime. The magazine would publish realistic reports from the war, describing the conditions in which the Lottas worked with the wounded and the fallen soldiers.

The Lotta Organization also published a Junior Lotta magazine, one of the first magazines directed to children. However, not very many copies were printed. In order to boost the morale of the Lottas working on the front, the organization published the Field Lotta Magazine.

In addition to the magazines, the Lotta Organization also published study books to support the work in the divisions, as well as rules and instructions.

Lotta Organization membership

Lotta Organization membership could be granted to a woman of at least 17 years of age who was loyal to the legal social order and was recommended by two well-known and trustworthy people. In the 1930s, a trial period was introduced for aspiring Lottas. During the 3−12-month trial period, aspiring members were provided with training on the principles of the organization and its activities, and on Lotta duties. At the end of training, the applicants sat a test, and successful applicants were allowed to join the organization. Each local Lotta chapter decided independently on the organization of the trial period.

In the mid-1920s, the Lotta Organization had around 47,000 members. By 1938, the number of members was more than 100,000. In wartime, the number of members continued to increase. In 1940, the organization had more than 130,000 members. By the armistice in 1941, the number of members was more than 150,000. The last confirmed membership figure is from 1943; the number of members was 172,755. If we include Junior Lottas in the 1943 figure, the number of members rises to 221,613.

Lotta Pledge

When women joined the Lotta Organization, they were asked to make the Lotta Pledge. Often, the Lotta Pledge was made in a church to a priest. The solemn occasion at the end of the Lotta training reflected the nationalist-religious values of the Lotta Organization. The pledge could also be made to the chairperson of the Lotta district or the local chapter.

The wording of the Lotta Pledge was changed many times over the years, but the principle message of the pledge remained the same. In 1943, the Lotta pledge read the following:

”I X.X. pledge with my word of honour that I will honestly and according to my conscience assist the Civil Guard Organisation in defending religion, home and fatherland, and fulfil the civil defence duties given to me according to the rules of the Lotta-Svärd Organization.”

Junior Lottas

In 1931, the Lotta Organization launched youth activities aimed at girls aged 8−17. The objective of the youth work was to convey the key values of the Lotta Organization to the young, thus preparing new members for the organization.

The members of the Youth Division, the Little Lottas, met at work evenings for lectures, discussions and crafts. They also participated in the activities of the Lotta Organization’s divisions whenever possible. In 1943, the name Little Lotta was changed to Lotta Girl. The reason for the change was that particularly older Little Lottas often carried out the same duties as adults, and the name Little Lotta was considered misleading. Nowadays the umbrella term “Junior Lotta” can be used to refer to both Little Lottas and Lotta Girls.

In wartime, older girls who participated in the work done locally to support the Defence Forces freed up Lottas to be posted for duties elsewhere.

Lotta Emblem

In the early 1920s, the Lotta Svärd Central Board commissioned Akseli Gallen-Kallela to design the Lotta Organization’s official emblem, but his proposal was rejected. Instead, a design by Erik Vasström was approved in September 1921. The chosen emblem featured the “Lotta Svärd” text on a blue swastika with heraldic roses – a motif very similar to the Civil Guard’s flag, with heraldic roses also having a connection with the coat of arms of Finland. At the time, the swastika was widely seen as a symbol of good luck, historically used in various contexts, including the Finnish Iron Age, medieval churches, and the Finnish Air Force.

The emblem appeared on Lotta pins worn on the collar of the Lotta uniform. Initially made of silver, the pins were later crafted from mixed metals and silver-plated from December 1940. Each pin was numbered, with the highest number in the Lotta Museum’s collection being 171,362. Unfortunately, these serial numbers cannot be used identify the pin’s owner.

Lotta Uniform

The official design of the Lotta uniform was approved by the organization in the spring of 1922. Before this, many local sections had used uniforms that the members had designed themselves.

Strict guidelines were in place regarding the use of the Lotta uniform. For example, the hem of the skirt was to be precisely 25 cm from the ground, the uniform was to be made from grey cotton or wool, and only Lotta pins and official course badges were to be worn with the uniform.

Dark coloured socks and shoes or ski boots were to be worn with the uniform. In the early years, the uniform included a coarse woollen cloak as an overcoat. Later, a lighter Lotta raincoat was added.

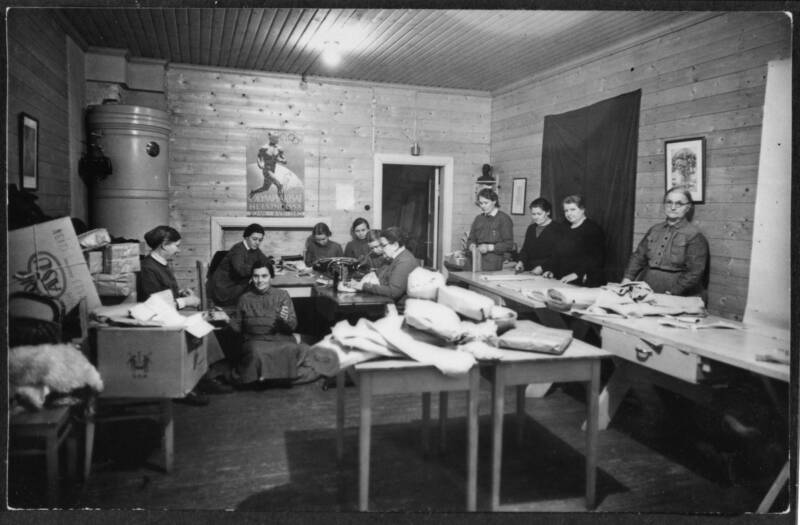

Work evenings

Local Lotta chapters were the core operational units of the Lotta Organization, with sewing evenings as their main activity. These gatherings occurred twice a month or even weekly in some areas and were crucial for reinforcing the group’s shared goals and values. Members were obligated to participate in these work evenings, with each Lotta required to complete at least 50 hours of service annually.

During these sessions, Lottas made and repaired equipment for the Civil Guard, including snow suits, backpacks, and ammunition belts. They also sewed Lotta uniforms and crafted items for sale or to be used as raffle prizes.

The Lotta Organization provided a work plan to guide these evenings, including lectures on history, women’s rights, civic duties, and temperance. Meetings also involved reading notifications from the organization and articles from the Lotta Svärd magazine.

Training in peacetime

The Lotta Organization’s systematic and extensive training efforts bolstered the organization’s nationwide operations, ensuring readiness even in exceptional circumstances.

Basic Lotta training was given at Lotta districts’ advisory events and in the recruits’ own localities. Division-specific courses were initially organized solely for members of the Medical and Catering Divisions. As demand for skilled Lottas increased, the training program expanded to include specialized training in various tasks. The first course aimed at members tasked with clerical and communications duties was organised in 1927, aerial surveillance courses began in 1930, with equipment maintenance training following two years later. Further training efforts were concentrated on division heads and district chairpersons, who were responsible for organizing both basic Lotta training and division-specific courses in their local areas.

The objective behind the training was to equip each division with uniformly skilled Lottas, enabling effective cooperation during crises.

Training in wartime

In wartime, the focus in training shifted to the special training of Field Lottas. Working in divisions enabled the Lotta Organization to lay a solid base for developing training activities. A wide range of Lotta courses was available, including training for aerial surveillance, office work, gas protection, civil defence, horse care, and youth work.

Training activities were partly determined by the need of the Defence Forces for Lotta work. The most labour-intensive training was for members who were part of either the Office and Communications Division or the Medical Division. Only Lottas willing to commit to being sent on field assignments after training were accepted for training.

Lottas working in the Medical Division received more training than Lottas in other divisions. Most of the members in the Medical Division had received at least two weeks of medical training. In addition to these short courses, six-month nursing assistant’s courses were also organised. Medical care required specific skills, which meant that courses in the Medical Division were more demanding than in other divisions.

Lotta Institutes

The Lotta Organization ran two Lotta institutes, which functioned as training centers for Lottas, reflecting the significance of training in Lotta activities. The Syväranta Lotta Institute on the Syväranta estate in Tuusula trained Lottas for leadership duties and special fields. From 1937 to 1939, activities at Syväranta included a boarding house as well as the institute. In 1940, the Lotta Organization acquired the Sorja estate in Karkku and ran a Lotta institute there from 1941. Among others, courses for Communications Lottas and Lottas working as wireless operators were organised at the Sorja Lotta Institute.

From 1937 to 1943, more than 2,500 Lottas were trained in the two Lotta institutes. Just before the Lotta organization was disbanded in the autumn of 1944, the organization donated both Syväranta and Sorja to the Finnish Women’s Aid Foundation.

Physical training

Physical training was an important part of the activities of the Lotta Organization. The objective of the organization’s physical training programme was to guarantee the best possible physical stamina on the home front and to make sure that the Lottas working in battlefield conditions were able to handle the stress related to life on assignment.

At the core of the Lottas’ physical training programme was obtaining the organization’s recreational activity badges. According to the instructions from 1925, a skiing and walking badge was awarded to a Lotta who, in one year, completed ten ten-kilometre journeys on foot or skis while carrying a 3 kg backpack. Three to five of the journeys could be made with skis, the rest on foot. In other words, in order to obtain one badge, they had to cover 100 km altogether.

In the early 1900s, there was fierce public debate regarding the suitability of women’s competitive sports. In principle, the Lotta Organization approved of women’s competitive sports, as long as it was restricted to sports suitable for women, such as gymnastics, rowing, Finnish baseball, orienteering, and skiing.

Relief work

Initially, the key task of the Lotta Organization was to support the work of the Civil Guards. The Lottas organised collections, gathered donations and volunteered for various auxiliary tasks. In 1938, for example, the Lottas put in 91,099 workdays for the Civil Guard and donated five million Finnish marks in cash.

However, during the depression in the 1930s, the relief work of the Lotta Organization extended to general social relief work. In addition to the Civil Guard, the Lottas began to help the Finnish Red Cross, the Mannerheim League for Child Welfare, the tuberculosis fund, as well as various hospitals, retirement home residents and local poor families. In addition to financial assistance, Lottas collected clothes and foodstuffs for disadvantaged people.

International cooperation

Already in the 1930s, the Lotta Organization was well connected internationally. Women’s voluntary civil defence work became a network that brought together countries along the Baltic Sea, and the network also included women from Norway.

However, during World War II, connections to the Naiskodukaitse in Estonia and the civil defence women in Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Norway were lost. Connections to the sister organization in Sweden continued throughout the wars. This cooperation consisted mainly of relief work sent to Finland by the Lottas in Sweden.

Business operations

It was obvious fairly early on that it would be impossible to base the finances of the Lotta Organization in the long term on collections alone. For this reason, determined measures were taken in order to develop the business operations that had begun with temporary canteens and catering at large events.

The Lotta Svärd Central Board had drawings prepared for kiosks and cafés to be built by the local chapters and the Central Board provided assistance in completing profitability calculations.

Kiosks, café and restaurants run by the local chapters became popular very quickly in the latter part of the 1930s, and by 1938, local chapters were running more than 250 different business operations.

Equipping field hospitals

In 1930, the Ministry of Defence sent the Lotta Svärd Central Board a classified letter asking the association to help equip field hospitals. Following this request, the Lotta Organization began to find equipment for eight field hospitals. The field hospital project was significant financially, and the cost of the whole project was FIM 3.6 million, or around EUR 1.2 million in current money.

Most of the field hospitals equipped by the Lottas were moved to the military districts’ warehouses during 1935. The hospitals remained the property of the Lotta Organization, and the organization was responsible for staffing the hospitals. In addition to the Lottas, the Finnish Red Cross equipped another eight field hospitals for the Defence Forces. During the Continuation War, the field hospitals were handed over to the Defence Forces.

Fortification construction sites

In 1938, Civil Guard members wished to do more to defend their country and volunteered to build fortifications. Fortification construction sites had been established immediately after the war in 1918 in the Karelian Isthmus, but it had not been practical to continue the work. The volunteer workforce restarted the work on the fortifications in July 1939. There were 29 construction sites across the Karelian Isthmus, divided into 14 regions, and some 3,0000 volunteers worked on the sites.

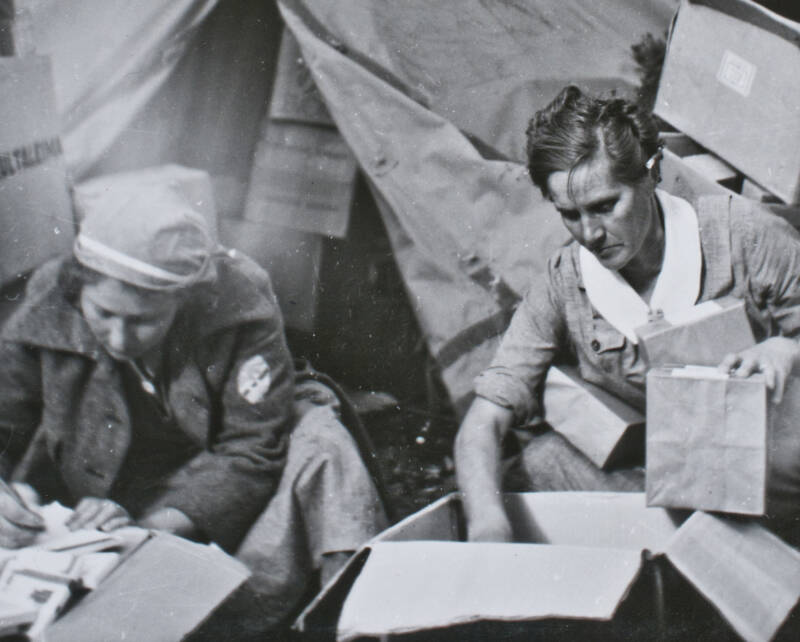

The Lotta Organization assumed responsibility for providing catering for the construction sites. The Central Board appointed Head of Catering Maja Genetz to oversee the task. Catering was provided at schools and Civil Guard buildings, and in tents in more remote areas. The Lottas worked for two weeks at a time, and around 200 Lottas were engaged in the catering work at any one time. In addition to providing catering, the Lottas organised field shops, or canteens, selling small, useful goods on the construction sites.

Home front

During the war, Lottas on the home front were busy feeding reserve forces traveling to and from the front, while also catering to war-fleeing evacuees, military police, war hospitals, and civil defense personnel. Lottas also managed provisioning duties at POW trains and camps.

On the home front, Medical Lottas assisted civilians and healthcare authorities, working in war and POW hospitals, convalescent homes, evacuation centers, medical depots, military pharmacies, and the blood service.

Additionally, home front Lottas handled office, communication, and control tasks, including aerial surveillance and field post, and were responsible for washing and mending equipment.

Lotta Svärd Border Office

When the war began, issues arose regarding the placement and use of Field Lottas, as there was no central organization to oversee their deployment. Without proper administration, many Lottas went to the front unsupervised, making it difficult to direct them where they were most needed. Additionally, the Lotta Svärd Central Board lost track of their members’ locations.

The Karelian Isthmus office, later renamed the Border Office, had successfully managed catering services during fortification construction. To address the organizational challenges, administrative responsibility for Lottas was centralized under the Border Office. Subdivided into regional units, it began overseeing Lottas going to the front and managing Catering Lottas at fortification sites, becoming a crucial link between the Defence Forces and the Lotta Organization.

The Border Office could efficiently and quickly deploy individual Lottas from rural areas to where they were needed most.

War zone

In the war zone, Lottas served under the Defence Forces, provisioning troops, treating the wounded, maintaining equipment, and performing office and communication tasks. As the war progressed, Lottas were increasingly needed for new roles, including clerks, wireless operators, switchboard operators, and cartographers.

Initially, Lottas under 20 could not be sent to the war zone without authorization from the Lotta Svärd Central Board. However, as the workforce shortage worsened, this rule was revoked, and even Lotta Girls as young as 16 were assigned duties.

The Lotta Organization made up about 40% of the women working under the Defence Forces. Additionally, six other women’s organizations, along with women obligated to work, also had volunteers in East Karelia.

Disbandment of the Lotta Organization

The war between Finland and the Soviet Union ended with the Moscow Armistice on 19 September 1944. The armistice imposed strict limitations on freedom of association and speech in Finland. Article 21 subjected Finland to external control over its domestic policy, forcing the disbandment of many organizations.

In response to the allied control commission’s request, the Civil Guard was dissolved in early November 1944. Since the Lotta Organization was tied to the Civil Guard, it too was slated for disbandment. To address this, the Lotta Svärd Central Board initiated a rule change to sever ties with the Civil Guard and began planning a foundation to continue its relief and aid work. These efforts were unsuccesful, however, and the Lotta Organization was disbanded on 23 November 1944.

Finnish Women’s Aid Foundation

In October 1944, the district representatives of the Lotta Organization held a meeting and decided unanimously to establish Finnish Women’s Aid Foundation and approved the rules drawn up for it. The duties of the foundation were defined as follows: […] to care for and assist women and children who are Finnish citizens, irreproachable in conduct, who have lost their health, guardians or jobs due to, or as a consequence of, the war, or who have to look after such persons, and who, in the spirit of Christianity, have acted on behalf of the home and the homeland.

The foundation was particularly willing to help the women returning from duties in the war zone. Some women returned to such hard conditions that they required urgent assistance in paying rent, collecting food portions, or buying equipment and tools to carry out their work. Members of the disbanded Lotta Organization could apply to the Finnish Women’s Aid Foundation for personal assistance.

Work Site Maintenance Association (Työmaahuolto Ry)

In early November 1944, a group of former Lotta Svärd Border Office managers established the Work Site Maintenance Association (later Työmaahuolto Oy) to employ women released from their Lotta duties. After the war, Work Site Maintenance provided catering services for state reconstruction sites in Northern Finland, where former Lottas put their skills and equipment to use.

Conditions on the Lapland reconstruction sites were harsh due to the scorched earth policy used by retreating German forces, which left up to 90% of the region’s infrastructure destroyed. The devastation covered an area nearly as large as Holland and Belgium combined. Work Site Maintenance had to navigate poisoned wells, mined roads, and deal with a shortage of cooking equipment. Accommodations were limited to huts and tents. Despite these challenges, the former Lottas were well-prepared, having experience working in difficult conditions.

Fate of the Lotta Organization’s assets

After the Finnish Women’s Aid Foundation was established, Lotta districts and chapters began donating their assets, including real estate, land, and movable property, totaling 340,500 old Finnish marks (EUR 58,870 in 2019). Additionally, profits of two million old Finnish marks (EUR 345,800 in 2019) from the Lotta Organization’s Border Office were transferred to the foundation. The Syväranta estate in Tuusula, now the Lotta Museum, was also donated.

Following the Lotta Organization’s disbandment, remaining assets were transferred to the state and, in 1952, given to the Alli Paasikivi Foundation, which supported social relief work. These assets included 60.3 million old Finnish marks in bank deposits and 14.7 million marks in stocks, totaling approximately 75 million marks (EUR 2,426,000 in 2019).

Thus, much of the Lotta Organization’s wealth was channeled through these foundations to support relief efforts for women and children, addressing significant post-war needs.

Staff canteens

Initially, Work Site Maintenance provided catering for state-run reconstruction site canteens, employing staff working on-site as well as trainers, cookery advisers, menu designers, and cashiers. By 1945, the company also managed several large company canteens, overseeing more than 250 by the summer. In 1947, Work Site Maintenance sold its state canteens and shifted entirely to the private sector, retaining 48 canteens.

In the 1960s, with a growing number of canteens, Work Site Maintenance established its own wholesale operation, Suuros Oy. By 1963, the company managed 110 canteens, designed industrial kitchens, and supplied ready meals from its central kitchen to canteens lacking cooking facilities.

By 1977, Work Site Maintenance had a turnover of 80 million, employed 1,800 people, and managed 130 canteens and 120 food distribution points.

Mass catering

One of the key operations of Work Site Maintenance was providing catering services for large public events. In the 1940s, Work Site Maintenance organised catering for several large sporting events. 98,000 people attended these events.

In the 1952 summer Olympics in Helsinki, Work Site Maintenance was responsible for managing the sports venues and outdoor restaurants built around Helsinki to cater for the visitors, as well as catering in the Olympic Villages and managing the 47 Olympic kiosks.

During the Olympics in Helsinki, the field provisioning units of Work Site Maintenance served a total of 600,000 portions of pea soup and 300,000 portions of meat soup. They served 400,000 glasses of milk and 500,000 sandwiches.

Tourism and catering operations

In 1952, Work Site Maintenance established its flagship restaurant, White Lady, in central Helsinki. Presumably, White Lady was one of the first restaurants in Helsinki to welcome women diners unaccompanied by men. With its continental cuisine, White Lady was very popular among the high society circles, as there were very few first-class restaurants in Helsinki.

In the mid-1960s, a sister company of Work Site Maintenance, Ravintohuolto, rented the estate of Viidennumero next to the famous bridges in Sääksmäki, with the idea of building a restaurant and tourism centre. In terms of business operations, the location was excellent; in addition to the busy main road, there were plans to build a pier for the Finnish Silverline cruise ships. The restaurant at Viidennumero had seating for more than 100 diners. Other services included a covered terrace restaurant, lake-side sauna, two dressing rooms and a service station. In the 1970s, Viidennumero was a very popular break area among tourists.

Ravintohuolto also managed hospital canteens. They were managed under the support association for heart and cancer patients (Sydän- ja syöpäpotilaiden Tuki ry). Ravintohuolto also managed canteens in the Children’s Hospital and the Radiation Therapy Clinic in Helsinki.

Vantaa production facility

In the 1970s, more and more staff canteens began to serve meals prepared in central kitchens rather than cooking the meals on site. Work Site Maintenance also built its own production facility in Vantaa.

For example, this facility had the capacity to produce 21,000 meatballs in an hour, or 168,000 meatballs a day.

The Vantaa production facility concentrated on producing meals for the nearly 90 staff canteens that Work Site Maintenance managed in the Helsinki area. As the range of products grew, new product groups, such as ready meals and frozen goods, changed the operations of Work Site Maintenance. The changes also introduced Work Site Maintenance to catering for airlines and schools.

Selling of Work Site Maintenance

In 1977, Work Site Maintenance and its sister companies adopted an umbrella name, Suuros Companies. At the same time, fierce competition in the sector and large investments drove Suuros Companies to a challenging situation. The Finnish Women’s Aid Foundation was forced to spend more and more funds to support Suuros Companies. Eventually, they decided to sell Suuros Companies in order to be able to spend their funds as the foundation had originally intended – to provide relief and aid to those suffering as a result of the war.

In 1978, Suuros Companies was sold to Oy Karl Fazer Ab, and soon after that, Fazer sold the Vantaa plant on to the City of Helsinki. Fazer held on to the chain of staff canteens with almost 200 branches.

Aid and relief work of the Finnish Women’s Aid Foundation

Soon after the establishment of the Finnish Women’s Aid Foundation, the foundation hired a relief secretary to plan and organise the relief and aid operations. Funds for the relief work initially came from the sale of the real estate and plots of land donated to the foundation. Later, relief work was funded by rent income from housing companies and funds received from the sale of restaurant operations.

Assistance was divided into three groups: assistance for sickness, assistance for vocational studies, and assistance for other personal matters. When allocating sickness assistance, the principle was to guarantee those with no means, primarily the members of the disbanded Lotta Organization, the best possible care, including specialist medical care if necessary. Most of the applications for sickness assistance were made for treating tubercular and rheumatic diseases. In the early years of the Finnish Women’s Aid Foundation, plenty of applications were made for assistance for vocational studies, but these applications continued to come in throughout the second decade of the foundation’s operations.

From The Finnish Women’s Aid Foundation to The Lotta Svärd Foundation

In 2004, the Finnish Women’s Aid Foundation changed its name to the Lotta Svärd Foundation. When the Lottas originally set up the foundation, they wrote the rules in a manner that allowed the foundation to also assist people who had not been members of the disbanded Lotta Organization.

In its time, the Lotta Organization focused on social aid and relief work, and the Lotta Svärd Foundation continues on that path. In addition to rehabilitation and assistance, the foundation promotes voluntary civil defence work with the focus on everyday safety. The foundation also maintains the Lotta Museum. The purpose of societal responsibility at the Lotta Svärd Foundation today and in the future, is to promote caring, support those in need of support, and provide a channel for doing good, while respecting the work and values of the Lotta organization and its members.

Rehabilitation for Lottas

Operations of the Lotta Svärd Foundation focus on providing rehabilitation and assistance to the members of the disbanded Lotta Organization, the Lottas and Junior Lottas, for as long as they need help. Every year, the foundation spends around EUR 3 million on rehabilitation.

Former Lottas and Junior Lottas may apply for rehabilitation offered by the Lotta Svärd Foundation. The rehabilitation is discretionary and can take place at home, or in a physiotherapy institution as inpatient or outpatient treatment.

Personal financial assistance and community grants

Former Lottas and Junior Lottas with limited means may apply to the Lotta Svärd Foundation for a grant to help with the cost of personal health care and medical costs. In recent years, most of the applications for financial assistance were made for purchasing glasses, for dental care and for medicine expenses. Every year, the financial assistance granted amounts to around EUR 500,000.

Since 1976, the Lotta Svärd Foundation has awarded almost EUR 6.5 million in community grants. Grants have been awarded to Suomen Lottaperinneliitto ry (the Finnish Association of Lotta Tradition), Maanpuolustuskoulutusyhdistys (the National Defence Training Association of Finland), Suomen Sotaveteraaniliitto (the Union of Finnish War Veterans), Rintamanaisten liitto (the Association of Women on the Front Line), Kaatuneitten Omaisten liitto (the Association of the Relatives of Fallen Soldiers), Naisten Valmiusliitto (the Women’s National Emergency Preparedness Association), and Sotainvalidien Veljesliitto (the Disabled War Veterans’ Association of Finland).

Rental housing

Following the war, there was a great need for housing in Finland and Helsinki, in particular. To alleviate this shortage, the Finnish Women’s Aid Foundation decided to build a large apartment building on Mannerheimintie road in central Helsinki. The handsome building entitled Oy Asuntoyhtenäistalo Ab boasted more than 300 apartments. The building also housed shops, offices, a laundry service, restaurant and day care centre. This building became the centre of activities for the Finnish Women’s Aid Foundation. Today, the Lotta Svärd Foundation owns around 60% of the apartments at Mannerheimintie 93.

In addition to this building, the Lotta Svärd Foundation owns rental apartments in Helsinki, Espoo and Tuusula. Income from the rental operations has played a central part in enabling the Lotta Svärd Foundation to continue its key task of providing rehabilitation and support to former Lottas and Junior Lottas. Rental income also enables the Lotta Svärd Foundation to continue to provide assistance and to maintain the Lotta Museum.

Lotta Museum

The Lotta Museum was opened to the public in the spring of 1996. Over the years, more than 360,000 people have visited the museum. The museum is famous for its high-quality services and versatile event productions. Adjacent to the museum is the Lotta Canteen, a popular museum café that offers home-baked sweet and savoury café products of high quality, as well as a daily lunch.

The Lotta Museum documents materials related to the activities of the Lotta Organization and of individual Lottas, in particular. The museum also has a duty to document the activities of the Finnish Women’s Aid Foundation and the companies operating under the foundation. In addition to documenting the past, the museum documents the work done to carry on the Lotta tradition and other Lotta-related phenomena of the modern day.

The Lotta Museum has a collection of artefacts, photographs, documents and teaching materials, a newspaper collection and a reference library. Most of the items in the collections have been donated to the museum. The collections are used in the museum’s exhibitions and activities, as well as by researchers, journalists, and enthusiasts interested in Lotta history. Today, adding items to the collections is determined in the museum’s collection plan. For the museum, the most valuable items in terms of information are items with a story or a documented link to phenomena of cultural and social historical value.

Lotta of the Year

Since 2007, the Lotta Svärd Foundation has nominated the Lotta of the Year. The Lotta of the Year can be a person distinguished in Lotta work, or a Finnish woman that has worked hard for the benefit of others in true Lotta spirit. The nomination may also go to a community that fulfils the above criteria.

The nomination is confirmed in December, around the Finnish Independence Day. The Lotta of the Year receives a certificate and a numbered piece of Lotta jewellery designed by architect Marja Hämäläinen.

Assets of The Lotta Svärd Foundation

After the Lotta Organization was disbanded, the Finnish Women’s Aid Foundation raised funds by setting up businesses to employ the former members returning from the war. The most significant of these enterprises was Work Site Maintenance (Työmaahuolto Oy).

Restaurant White Lady was sold in 1977. Funds acquired from the sale were invested profitably, and the dividends have provided rehabilitation and assistance to the members of the disbanded Lotta Organization, the Lottas and Junior Lottas until today.

In the 2000s, the Lotta Svärd Foundation has spent around EUR 50 million in total on rehabilitation and assistance to the former Lottas and Junior Lottas and on community grants. Every year, a total sum of around EUR 3.5 million is spent on rehabilitation, assistance and other support measures. In addition, the foundation maintains the Lotta Museum and upholds the Lotta tradition.

The activities of the Lotta Svärd Foundation are regulated by the rules of the foundation and the Foundations Act. According to the rules of the Lotta Svärd Foundation, there is no fixed term for the foundation’s activities; they will continue in the future.

Three cornerstones of strategy

The values of the Lotta Svärd Foundation date back to the work of the Lotta Organization established at the beginning of the 1920s to support the Finnish society. The Lotta Organization and later the Finnish Women’s Aid Foundation provided training and assistance, enabling women to participate actively in the building of the Finnish society.

It is the objective of the foundation to continue on the path paved by the Lottas. This is why the Lotta Svärd Foundation wishes to play its part and take responsibility for the Finnish society and to help young people develop their sense of societal responsibility today and in the future.

The foundation will continue to prioritize training women for crisis situations, providing assistance, maintaining the museum, and promoting the Lotta tradition.

Everyday safety

Together with its stakeholders, the Lotta Svärd Foundation participates in projects that promote overall safety.

To promote everyday safety, the Lotta Svärd Foundation works with the Women’s national Emergency Preparedness Association, among others. The objective of the association is to develop women’s skills related to safety and preparedness through training, and to improve women’s opportunities to work for society in exceptional circumstances.

Support and assistance

The Lotta Svärd Foundation embodies responsibility through its dedication to caring for those in need. The impact of the assistance provided is significant, as are the projects managed every year. Each year, the foundation’s assistance programs provide crucial support to Finnish nationals affected by war or other crises, with a special focus on women and children.

Former members of the disbanded Lotta Organization, the Lottas and Junior Lottas, will continue to be at the core of the relief and assistance work for as long as they need help. After this, in accordance with the rules of the Lotta Svärd Foundation, the activities will focus on women and children in need of help.

Preserving cultural heritage and continuing the Lotta tradition

The Lotta Svärd Foundation maintains, and will continue to maintain, the professionally managed Lotta Museum. The museum’s objective is to showcase the societal responsibility of the Lottas and Finnish women, highlighting their contributions to the betterment of society during their time.

To uphold the Lotta tradition, the Lotta Svärd Foundation works with Suomen Lottaperinneliitto ry (the Finnish Association of Lotta Tradition). The association was established in 1992 to carry on the Lotta tradition, share knowledge about the Lotta Organization’s activities, promote the will toward national defense, better prepare women for exceptional circumstances, and support research and literary works related to the Lotta Organization. The Lotta Svärd Foundation also supports various projects related to the continuation of the Lotta tradition, at the discretion of the Board of Directors.